Dear Africa Brief,

Special Edition: Africa and the war in Ukraine

In March 2022, I first considered the Russian invasion of Ukraine with an eye for the impacts it will have on the African continent, its states and its people.

We return to this story for two reasons: first, as Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba visits Africa in a bid to counter Russian diplomatic influences on the continent, promising to send “boats full of seeds for Africa.” His trip has been cut short since Russia’s latest offensive. The second reason concerns the United States UN Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield's accusation that Russian mercenaries are exploiting natural resources in the Central African Republic, Mali, Sudan, and elsewhere in Africa and the Middle East to help fund Moscow’s war in Ukraine. At the start of 2023, Foreign Minister Lavrov visited a host of African countries. And just last week a Russian frigate, the Admiral Gorshkov, docked in Cape Town ahead of joint military drills with South Africa and China.

Discussion on this topic must start back at the UN General Assembly’s vote on the denunciation of the invasion of Ukraine. Of the 194 member votes cast, 141 voted for the resolution, 35 abstained, and five voted against (one of them being Eritrea). Many of those states abstaining and voting against the resolution were African; Algeria, Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

Since this vote, Western powers and Russia have exchanged allegations that the other is responsible for the war's impact on food shortages on the continent. In a confidential report circulated among diplomats in Brussels, European officials suggested: “It is not enough to say that ‘EU sanctions are not responsible for the food crisis’, we need more substance and sharper LTTs (lines to take), including from EU Headquarters.”

We return to this topic today as pressure mounts on African states to pick a side. In this briefing we consider reasons for African states’ current diplomatic posture, both contemporary and historical.

Africa in the Cold War

Russia—Africa relations draw their roots from the cold war, decolonisation, and Africa’s liberation movements. Allowing for some conflation of the USSR with Russia, between the 1950s to the 1980s, Africa became a stage on which the USSR and the United States embarked on proxy wars and economic machinations to assert their geopolitical influence. As a consequence, the Soviet bloc’s support for African liberation movements is instructive of present day Russian relations.

Again allowing for some reductive history, the USSR positioned itself as an alternative to ‘Western imperialism’ with many African liberation leaders finding ready allies in the Soviets. Among them, Algeria, Guinea, Ethiopia, South Africa (the African National Congress), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (prior to Mobutu Sese Seko), Angola and Mozambique received financial and military support from the USSR. Conversely, the United States and European powers often found themselves supporting despotic regimes in the name of preserving democracy and the free market. History hasn’t looked too kindly on some of the unsavoury characters and governments the US and its allies chose to support, including, the Apartheid government, Angola’s Jonas Savimbi, and the Congo’s Mobutu Sese Seko.

In stark contrast, the USSR found itself associated with more revered African statesmen, including the first president of the DRC, Patrice Lumumba, Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah. As for Patrice Lumumba, the C.I.A helped in his assisination. Such was the significance of his death that Belgian author Ludo De Witte called it the “most important [impactful] assassination of the 20th century.”

When those liberation movements succeeded in overcoming the British, French, and Portuguese, many post-colonial African states adopted the economic policy and political ideology of the USSR.

Today, pro-Russian sentiment has gradually increased in Africa, particularly in former French colonies. As readers of this Brief will know, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine comes at a time when relations between Mali and its West African neighbours with France have frozen over, with many West and Central African states pivoting to military support from the private Russian company, the Wagner Group. This truly truculent troop is known for its flagrant human rights abuses — unsurprising considering the Russian military’s bombing of a maternity hospital in Ukraine.

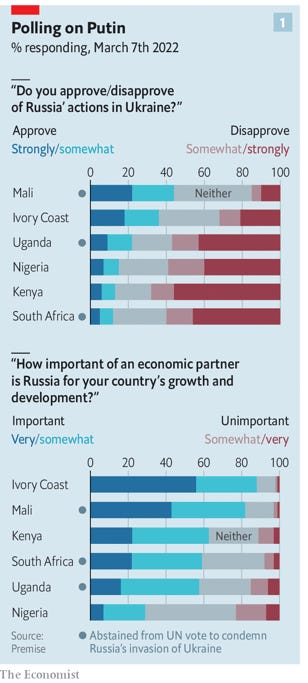

All of this, however, is not to suggest support for Russia is uniform across the continent, not in the least (see the polling graph below). Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria have all spoken out against the escalating conflict. Kenya’s ambassador to the United Nations made a rousing speech at the United Nations Security Council comparing the Ukraine conflict to Africa’s colonial past.

Weapons and Wheat

Whereas the USSR approached the continent as partners in an ideological struggle against imperialism, today Russian foreign policy treats the continent as a passive theater for its geostrategic interests. This is a fact, Joseph Siegle argues, demonstrated by the series of asymmetric (and often extralegal) measures Russia deploys, including: mercenaries, arms-for-resource deals, opaque contracts, election interference, and disinformation. If this isn’t proof enough, Russia’s invasion of a sovereign Ukraine proves its imperial ambitions.

Whereas other global powers (especially the US) chose to partner with African states, Moscow has opted for an elite-led approach, supporting many unpopular and illegitimate leaders to stay in power. Moscow does so by engaging two levers — weapons and food. On the former, Russia outcompetes China, France and the US in arms exports to the continent. Moscow has taken particular interest in Africa’s Northern and Western states, propping up regimes on NATO’s southern flank.

When not supporting states for their geostrategic importance, Russian arms flow to Central and Southern African governments often in exchange for mineral rights. In these places, its industries and mining companies have interests in the extraction of cobalt, coltan, gold, oil, copper, and nickel.

Of recent focus to the Kremlin are Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique. It was no coincidence that as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began, the deputy leader of Sudan’s junta, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagolo, led a delegation to Moscow to strengthen closer ties between the two countries (Russia has gold mining and other mineral concessions in Sudan). It is alleged that hundreds of tonnes of illicit gold from Sudan has flowed to Russia over the years to fortify Russia’s “fortress economy.”

Evidence of Russia's ties with African states is the 2019 Russia-Africa summit which saw 43 African leaders join (a better turnout than the UK and France’s Africa summits).

“Every society is three meals away from chaos”

Russian and Ukrainian agricultural exports account for 14% of global maize, and 58% of sunflower oil. Ukraine is also a top global exporter of corn, barley, and rye. Major importing countries of these staple foods are African, including: Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Nigeria, Tanzania, Algeria, Kenya and South Africa. Libya imports some 43% of its total wheat consumption from Ukraine. At the start of the conflict, Egypt banned the export of wheat and several other food products to secure its rations.

There is now almost no doubt that the increasing food prices are going to have significant effects on the continent. But food price increases cannot only be attributed to the war in Ukraine.

The war has precipitated a trend in African food markets with a divergence between supply and demand in these markets happening for some 3 decades. Africa’s food import bill has increased by about US$35.7 billion over the past quarter century—from US$7.9 billion during 1993–95 to US$43.6 billion during 2018–20 (World Bank). The price of bread has increased due to a reduction in wheat exports from Ukraine but also as a result of weather patterns with severe droughts in East Africa and production declines as a result of the war in Ethiopia.

In this context, the war induced price shocks and resulting hunger are likely to make an already weak economic recovery from the pandemic significantly worse. This will have knock-on effects. Foreign Policy warning that “price spikes and food insecurity could inflame conflict, heighten ethnic tensions, destabilize governments, and cause violence to spill over borders.”

As the Economist writes; “across sub-Saharan Africa food makes up roughly 40% of the consumer-price basket. Food inflation, which had been running at about 9% a year in 2019-20, started ticking up a year ago to reach 11% in October because of rising transport, oil and fertilizer prices and disruptions to farming from the pandemic.”

Professor Abdul-Ganiyu Garba, a Nigerian economist, opines "if there is an increase in crude oil prices, inflation will grow globally and the cost of most of our [Africa’s] imports will also rise, which will transfer to domestic crisis."

Spoils of War?

Still, there are some African countries who will gain. With increased oil prices Africa’s oil producing economies of Nigeria, Libya and Angola would benefit from an oil embargo on Russia. Libya has the ninth-largest known oil reserves, but is frequently subject to militia blockades, hampering its output.

In the medium term, Algeria’s oil and gas pipelines will benefit as Europe tries to get off its addiction to cheap Russian fossil fuels.“The big prize would be European support for one of two mooted gas pipelines that could link Nigeria to Morocco and go on to Europe, or Nigeria to Algeria through the Sahara” (the Economist).

With fears of stagflation, South Africa’s mining giants are bound to cash in on the export of platinum, gold, nickel, and copper. While the country’s coal miners will find renewed interest from European buyers.

Ethiopia’s large wheat fields could gain from supply shortages — however the country needs to solve its own production problems precipitated by its recent civil war.

Left behind and let down

The immediate impact of the invasion in March 2022 was the plight of African students in Ukraine. Some 20% of Ukraine’s foreign students were African. Moroccans make up the largest group with 8,000 students, Nigerians are second with 4,000 and Egyptians are third with 3,500.

African governments had to move quickly to charter evacuations of their citizens. Unfortunately reports of racism by Ukrainian and Polish border guards and the denial of access to bomb shelters have emerged. In one video viewed over two million times, a crowd of Nigerian students can be seen pleading with armed border guards. Some kneel on the ground shouting, “We are students. We don’t have arms.”

Diplomacy

Historic and present factors considered, what of diplomacy between Africa’s regional blocs and individual states towards Russia? To start at the continental level, on Feb. 24 2022, AU chair Macky Sall and AU Commission chair Moussa Faki called on Russia and Ukraine to establish a ceasefire.

Most interesting has been South Africa’s (a BRICS’ member) flip-flopping position. On Feb. 23 the country asked Russia to withdraw its troops from Ukraine and called for a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Soon thereafter the Russian Foreign Ministry shared a formal communication with South Africa’s Department of International Relations, effectively reminding the ruling party, the African National Congress, that Russia supported the fight against apartheid while the US and UK were complicit in propping up the apartheid regime. In a series of social media posts, the Russian embassy highlighted Moscow’s role in financial support and military training to the ANC and its armed wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe.

The move, along with South Africa’s complete energy dependence, swayed the country to abstain from the UN General Assembly vote on March 2.

Since then, in the September meeting between President Biden and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, President Ramaphosa raised objections to a draft U.S. bill that would sanction Africans doing business with Russian entities that are under U.S. sanctions. The Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Bill, would monitor African governments’ dealings with Russia. South Africa’s Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor has been called “Cold War-esque” as well as described as “offensive.”

Speaking to President Biden, Ramaphosa said African states should not be punished for their historic nonaligned position, saying “We should not be told by anyone who we can associate with.” This message was hammered home in the UNGA address by AU Chairperson and Senegal’s President, Macky Sall.

Where to next?

Similar to the cold war, Africa finds itself reeling from the impacts of hot and cold wars far away between nuclear powers. Dissimilar to the bipolar era, however, the continent today can look for solutions within, relying on the African Free Continental Trade Agreement, domestic innovations, and regional solidarity to get it through the undoubtedly difficult years to come. At the very least, let us hope that Putin does not enjoy the company of many African leaders at the next Russia—Africa summit.